The longer days of summer offer desk jockeys like me a seasonal opportunity for direct sunlight. After work, I like to go swimming. But my local pool, like too many others across Australia, has fallen into a dire state of disrepair.

Wed 14 Jan 2026 06.00

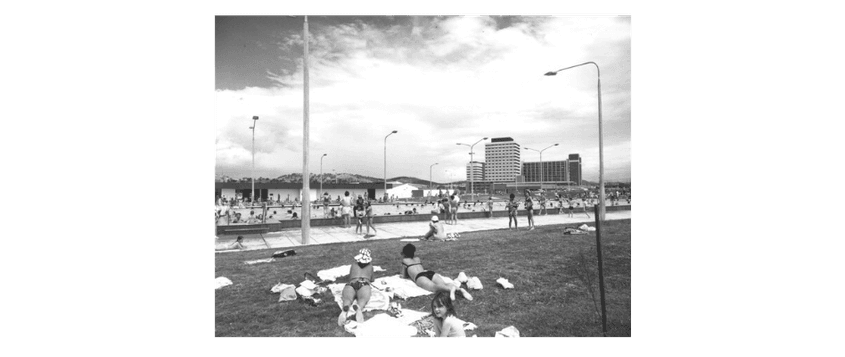

The Olympic swimming centre, Woden Town Centre, opened for the 1971 swimming season. Courtesy ACT Heritage Library, ACT Administration Collection, 005656, Nov 1971

At the Phillip Swimming and Ice Skating Centre, in Canberra’s south, the turnstiles stopped turning years ago.

A sign on the ticket booth points the way through a tunnel of temporary fencing, to a kiosk that hasn’t handled a hot pie since a Four ‘n Twenty went for two and fifty.

The art deco clock hanging above the entrance to the change rooms ticked its last tock at 6:40 on some indeterminant day before the pandemic. Although the change room has ample room for dozens of people, today it’s just me and a leaky shower.

The chipped concrete means no child would want to run around the pool anyway, and my attempt to jump in off a diving block is thwarted by a restive lifeguard. He informs me the blocks are ‘out of order’ because the concrete is so loose that they just might tumble into the water behind me.

But the water is cool, the gardens are shaded, and entry was just seven dollars. In the midst of a heatwave, this is an oasis.

The Olympic swimming centre, as it was then known, was built by the Commonwealth Government in 1971. But in 2008 the ACT Government sold the pool to a private company. In 2022, after years of neglect, it was on-sold to a real estate developer. It’s just one in a cluster of recreational facilities – the basketball courts, the bowling greens, the pitch n’ putt – sold off since the area was rezoned for commercial purposes.

Just before Christmas, the ACT Government granted the developer approval to build the first of a set of towers that will see what’s left of the pool finally demolished. In a meek concession, the developer will be required to build a publicly accessible 25-metre pool – indoors, underneath the towers. Just how and why that agreement was come to is the subject of an inquiry by the ACT Audit office.

My experience might be local, but the state of our public pools is a national problem.

Last year, an ABC investigation found that more than half of Victoria’s council-run pools are over 50 years old, at which point they start to need a lot of investment to stay open.

A 2024 report from Royal Lifesaving Australia estimated that, without an $8 billion reinvestment, 500 public pools across Australia could be closed in the next ten years. The report points out that it is usually local governments that pick up the tab for public pools, but there are serious questions about the financial future of local governments, many of which ultimately rely for funding on a Commonwealth that is reluctant to raise revenue.

By 2065, Canberra’s population will have grown by 300,000 more people. And the number of extremely hot days will only increase. Yet the ACT is cutting the number of public pools – my local isn’t the only one. So where will people swim?

The Royal Life Saving Australia report argues that pools generate over $9 billion in social, health and economic benefits. But this shouldn’t be about money. Public pools might never make money, but they will always be valuable.

They are just the kind of thing that make places like Canberra stand out on those coveted ‘world’s most liveable city’ indexes. But Canberrans are looking at a future in which more and more people live in more and more apartments with fewer and fewer places to exercise, congregate and relax. While the price of those apartments relentlessly increases, the worth of living in the area declines.

George Monbiot argues that, instead of private luxury and public amenity, we should aspire to public luxury and private amenity. But we’re replacing public amenity with, well, tiny apartments. Most people can’t afford to have a pool in their backyard, but together we could invest in a public pool that everyone can use.

The closure of this kind of public infrastructure not only makes our cities and towns less desirable to live in, it cuts off opportunities for people to share the common experiences that help form the bonds of community.

I prefer backstroke, as it helps work out the knot tied in my shoulder from hunching over a hot computer. But in between the lane ropes I had to squint into the setting sun glinting off the black glass of the high-rise tower over the road. Next summer, the same developer will have broken ground mere metres from the shallow end. I guess I’ll just go jump in the lake instead.