Temporary workers from Pacific Island nations and Timor Leste generate almost $1 billion in economic value, but less than $200 million ends up going home with them.

Tue 10 Feb 2026 10.00

AAP Image/Poppy Johnston

The Pacific Australia Labour Mobility (PALM) scheme is a ‘guestworker’ program that allows people from nine Pacific Island nations and Timor Leste to work in low-waged occupations across rural and regional Australia. There are currently more than 31,000 PALM workers in Australia on visas that can be valid for up to four years.

The PALM scheme is supposed to be a ‘win-win’: Australia gets people to do jobs that are hard to fill, and the Pacific gets the money sent home by people working in Australia. Official statements – from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the Minister for International Development and the Pacific – highlight the contribution that remittances make to the economies of nations that send PALM workers to Australia, but where does the money generated by these workers actually end up?

It’s hard to find information about exactly who is earning what from the scheme. But the scant amount of data that has been published – one DFAT slide, a study by the World Bank, and official guidance from Australian Aid – shows that the broad majority of the money earned by PALM workers stays in Australia.

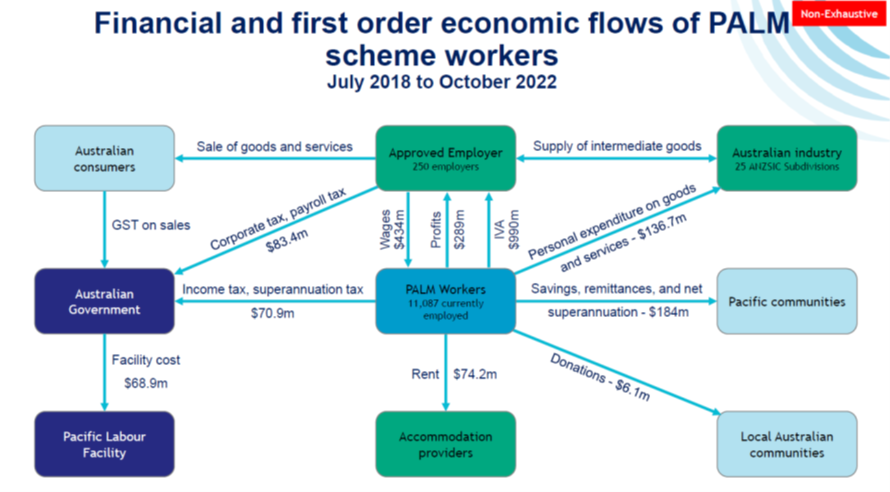

A presentation made by DFAT at the 2022 Australasian Aid Conference indicated that the total ‘Industry Value Added’ from the PALM scheme was $990m. Of this, just $184m was saved and remitted to the Pacific and Timor Leste – this included money earned as superannuation, which people can have trouble accessing once they leave Australia. The rest – $806m – remained in Australia.

Figure 1: The 2022 DFAT slide, from the presentation ‘The Long-Term PALM Scheme: Triple Win During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond’

If this slide is accurate, over 80% of the economic benefit went to Australia, the wealthiest country in the region, while about 18% went to workers from some of Australia’s poorest neighbours. This means Australia makes more than four times as much off the back of PALM workers as the rest of our ‘Pacific family.’

It is important to note that this DFAT snapshot is limited to the 11,087 workers that were in Australia between July 2018 and October 2022 (and some of them on an earlier iteration of the scheme). But these figures are broadly corroborated by World Bank survey estimates, which suggest that between 65% and 78% of PALM workers’ post-tax income is spent in the Australian economy.

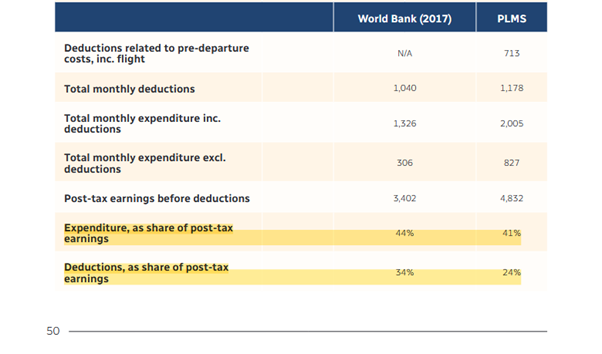

Figure 2: This 2023 World Bank study ‘The Gains and Pains of Working Away from Home the case of Pacific workers and their families’ shows that between two thirds and three quarters of what PALM workers earn stays in Australia.

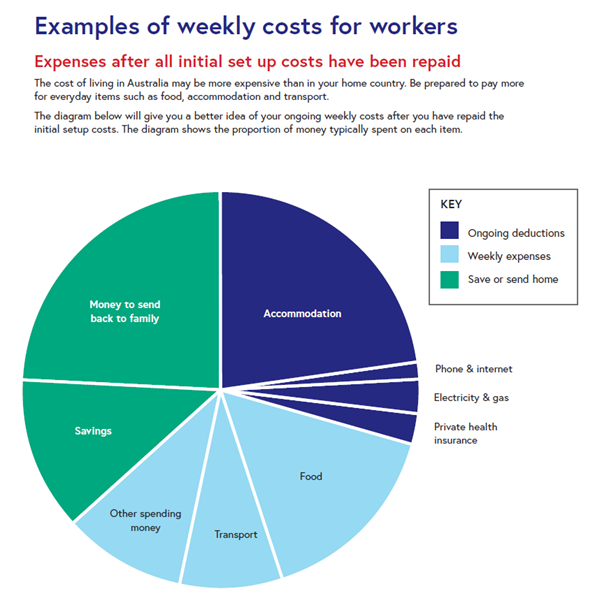

Moreover, the Australian Government’s official advice to PALM workers is that most of their money will stay in Australia. A guide to the payroll deductions permitted under the PALM scheme tells people that about one third of what they earn can be saved or sent home. This is partly because employers who hire people under the scheme are allowed to deduct the cost of things like flights, visas, and transport, and partly because the high price of private health insurance, rent, and other basics.

Figure 3: Official advice given to PALM workers, from the document ‘PALM Payroll deductions explained’

The uneven distribution of these economic spoils is only the start of the inequality baked into the design of the PALM scheme. PALM visas conditions are more restrictive than any other work visa in Australia’s migration system.

Participants cannot easily change employers, have no rights to family accompaniment, and possess no pathways to residency. Because of these restrictive conditions, an estimated 7000 people have made the difficult choice to leave their employer and try and survive in Australia in breach of their visa conditions.

In fact the problems are so bad that the scheme has been identified as a Modern Slavery risk by both the NSW Anti-Slavery Commissioner, and the UN’s Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of slavery.

Since the DFAT presentation was made in 2022, the number of participants in the PALM scheme has tripled, which means it is likely that the gulf in benefits between Australia and its Pacific neighbours has grown. If so, the Australian Government’s claims that the PALM Scheme has positive developmental and diplomatic benefits look dubious.

If these problems are not addressed, the Australian Government could have a very hard time working with “our Pacific family” on other issues. As Vanuatu’s Labour Commissioner told The Australia Institute, “our workers are people, not commodities”.

You can hear stories from the Pacific Islanders who have worked in Australia under the scheme in the four-part Australia Institute podcast PALMed Off.

The MAGA movement is synonymous with Donald Trump, but experts say it’s become so “battle-hardened” it’s likely to endure long after the US President leaves office.