One of the big announcements at last week’s UN climate talks in Brazil was that the South Korean Government has committed to phasing out coal-fired power by 2040.

Wed 26 Nov 2025 00.00

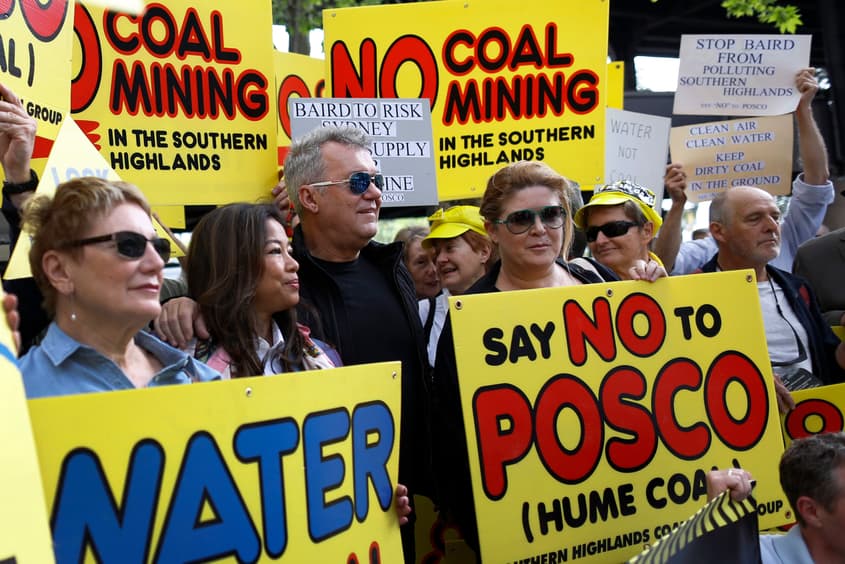

Photo: Jimmy Barnes (centre) stands with members of the Southern Highlands community during a protest demanding that the Posco owned Hume Coal pull of a proposed coal mine in Sutton Forest. (AAP Image/David Moir)

One of the big announcements at last week’s UN climate talks in Brazil was that the South Korean Government has committed to phasing out coal-fired power by 2040.

This is a big deal. Not only because it will reduce the substantial emissions of Korea, but because of the influence it will have on the other big Asian coal importers – China and Japan. There are centuries of rivalry between these countries and one of them moving to phase out coal will help move the others forward.

But this globally significant news might not have been possible were it not for grass roots environmental activism in New South Wales.

Three major South Korean companies had planned coal mines in NSW over the last decade. All three were defeated by local community opposition.

The first of these mines to fall was the Bylong Coal Mine, planned for the Bylong Valley, southwest of the Hunter Valley. It’s a particularly beautiful part of NSW, with sandstone cliffs towering over some of Australia’s most innovative and sustainable farms.

Korea’s state-owned electricity generator KEPCO was behind the Bylong proposal, but after years of fierce local opposition by the Bylong Valley Protection Alliance and others, the mine was sensationally rejected by the NSW Independent Planning Commission (IPC) in 2019. The IPC cited local impacts and climate as key reasons for the decision.

Another proposal was the Hume Coal Mine in the NSW Southern Highlands, pushed by one of Korea’s biggest companies, POSCO. This was bitterly opposed by farmers, tourism businesses and lovers of the area as diverse as Alan Jones and Jimmy Barnes.

Rallies, locked gates, legal action. Local groups like Coal Free Southern Highlands threw everything at defending this area from POSCO. They finally won with the IPC rejecting the mine in 2021.

The Wallarah 2 mine was pushed by the South Korean Government-owned KORES for the NSW Central Coast, near Wyong. The proposal to mine for coal under the region’s water resources appalled locals from the mid 2000s and spurred the founding of the Australian Coal Alliance.

The dramas surrounding the Wallarah 2 mine cannot be summarised in a paragraph. Suffice to say, it contributed to the downfall of many NSW Government Ministers, including former Premier Barry O’Farrell and led to a complete re-write of major project planning guidelines. While it was approved in 2018, it has never been developed.

These projects received at least tacit support from the NSW Government and NSW Department of Planning. Had they gone ahead, all of them would have been subsidised by the Federal Government’s Fuel Tax Credit Scheme. Community opposition was critical in ensuring that they did not proceed.

Combined, these projects would have seen Korean companies invest $3.6 billion in mines that would have produced 13 million tonnes of coal each year. They would have seen the Korean Government deeply invested in Australian coal mines planned to operate into the 2050s.

Instead, none of them exist. Zero dollars were invested. Zero tonnes of coal are being produced and shipped to Korea. Korean ministers and executives lost no face in walking away from these non-existent investments. No unions have to petition governments to save the jobs in the non-mines.

This demonstrates the importance of local, grass-roots climate activism. This shows the global impact that local groups can have in this interconnected world. More than this, however, it shows the importance of opposing mines and gas fields by climate activists.

Governments and mining lobbyists claim that it is only important to reduce the demand for coal. They say that if we don’t dig it up, someone else will.

Korea’s decision shows that this is wrong. It shows how coal mining projects and coal-fired power projects are closely linked. Korea is able to reduce coal demand because its companies are not locked in to major investments in coal supply.

Both the supply and demand of fossil fuels are important for climate action. Even where there is not such integration between mines and utilities, restricting supply keeps coal prices higher, reducing the demand for it. As some researchers put it, reducing emissions from fossil fuels involves cutting with both arms of the scissors.

Australia may have lost the race to host the next big climate conference, but Korea’s decision and its links to Australia show that it is not conferences that will solve climate change. Much more important is Australia’s role as a fossil fuel exporter and supporting local people to do something about it.