Tue 18 Nov 2025 22.30

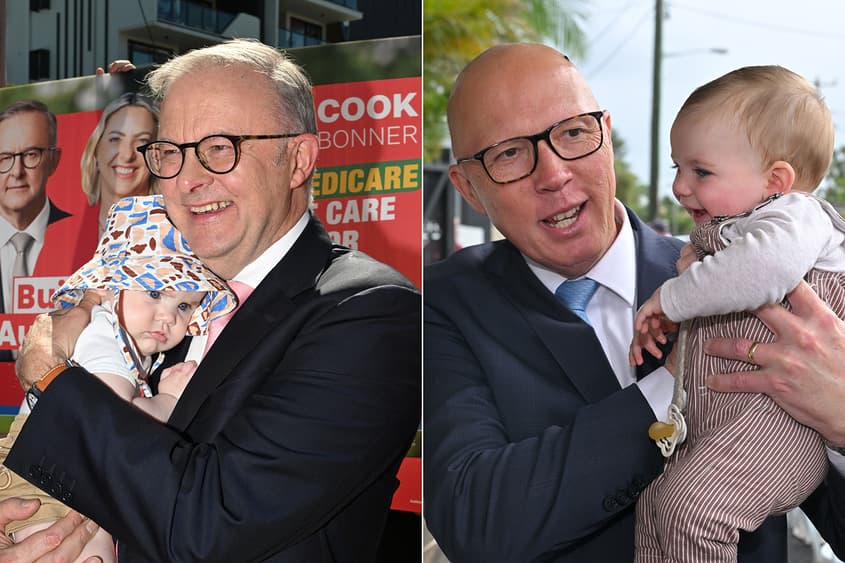

Photo: AAP Image/Lukas Coch, Mick Tsikas

The Claim: “Labor received just 34 per cent of the primary vote and owes its thumping parliamentary majority to another structural factor – Australia’s preferential voting system.”

That’s according to the Australian Financial Review’s editorial about the implications of Zohran Mamdani’s victory in the New York City mayoral election.

It is true that Labor received just 35% of primary votes, but won a “thumping” 62% of House of Representatives seats.

It is not true that preferential voting is the reason for Labor’s majority.

Preferential voting is not the reason for Labor’s ‘thumping majority’

The idea that, if preferences were removed from the equation, Labor’s parliamentary majority would be significantly smaller (or non-existent) has been popular in right-wing social media circles since the 2025 election.

But, as psephologist Dr Kevin Bonham has pointed out, Labor led on primary votes in 86 seats of the 94 seats they won, meaning they’d still have a historically large majority regardless of preferences.

Preferential voting is a proud Australian institution, going back over one hundred years. It gives Australian voters more choice and means you can never “waste” your vote, but what it cannot do is explain Labor’s landslide victory in the 2025 election.

Verdict: Not true

What is behind Labor’s disproportionate win?

If preferential voting caused these disproportionate results, we would expect to see a first-past-the-post system like the United Kingdom’s deliver more proportionate election results.

However, the opposite is true.

In last year’s UK election, the Labour Party won 63% of seats with just 34% of the vote. In a first-past-the-post system like the UK’s, the voter ticks one box: they do not get to indicate which other candidates they prefer over the rest. If their preferred candidate is out of the running, their vote gets thrown out – even if the winner received far less than a majority.

Australia, with preferential voting, had less distorted results than the UK with first-past-the-post voting.

The explanation for the UK and Australia’s distortion is the same: single-member electorates. In both countries, only one member of Parliament (MP) represents each seat.

Single-member electorates turn national elections into 150 ‘winner-takes-all’ races, meaning where votes come from matters just as much as the number of votes a party receives. For example, if the Australia-wide result in 2025 – Labor receiving 35% of primary votes and 55% of the two-party-preferred count – was repeated identically in all 150 seats, then Labor would have won 100% of them. That’s despite almost two-thirds of the country not putting them first on their ballot.

In reality, votes are not spread evenly throughout the country, but it’s that ‘winner takes all’ model that allowed Labor to get such a big majority with just over a third of the vote.

The problem has become more noticeable as Australians have increasingly lost faith in the major parties. The 2025 election was the first where more people voted for non-major party candidates than the Liberal–National Coalition, and it had the largest gap between vote share and seat share for the winning party in recent Australian history.

An alternative to ‘winner takes all’ is proportional representation, where parties and candidates win seats based on their share of the vote. Proportional representation is already used in the Australian Senate (where seat share much more closely matches votes), as well as in New Zealand, Tasmania, and the ACT.

So while the AFR was wrong about preferential voting, what is true is that the electoral system does produce distorted outcomes, by design, but the fact is preferential voting has nothing to do with it.