Fri 5 Dec 2025 06.00

Photo: AAP Image/Dean Lewins

Australia’s health system is under strain. Public hospitals, the private sector, and primary care – like Tolstoy’s unhappy families – are all struggling in their own way.

The reason is simple. Ours isn’t a health system. It’s an illness system: too reliant on hospitals and specialists, neglecting prevention and primary care, ill-suited to modern health needs.

And the consequences are becoming impossible to ignore.

According to the latest OECD statistics, we spend 10.3% of GDP on health care compared to the OECD average of 9.3%. Health services consume 20% of all government spending – the fourth highest share in the OECD. Yet our spend on prevention is below the average (and shrinking, it would seem).

Per capita we’ve more CT and MRI scanners. We also have more doctors, but the distribution is wrong, hence our GP shortage. So, while our mortality rates after acute events like stroke are among the best, avoidable hospitalisations sit 30% above the OECD average.

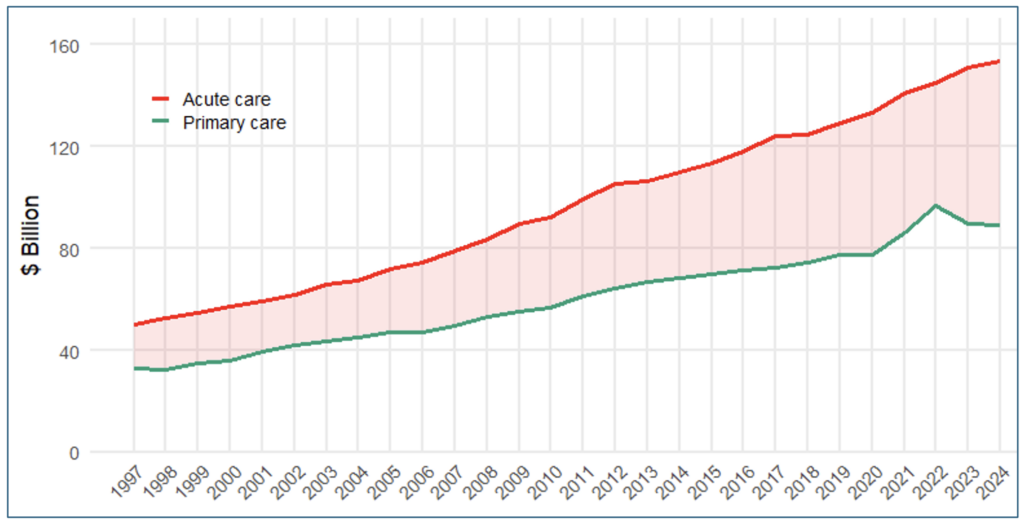

We are edging toward a US-style model: the fifth-most expensive system in the OECD, with spending on acute services growing faster than primary care – without making us healthier.

Constant prices. Acute care combines total expenditure (public and private) on hospitals, capital, and referred services. (L Slawomirski. Source: AIHW Health expenditure Australia 2023-24)

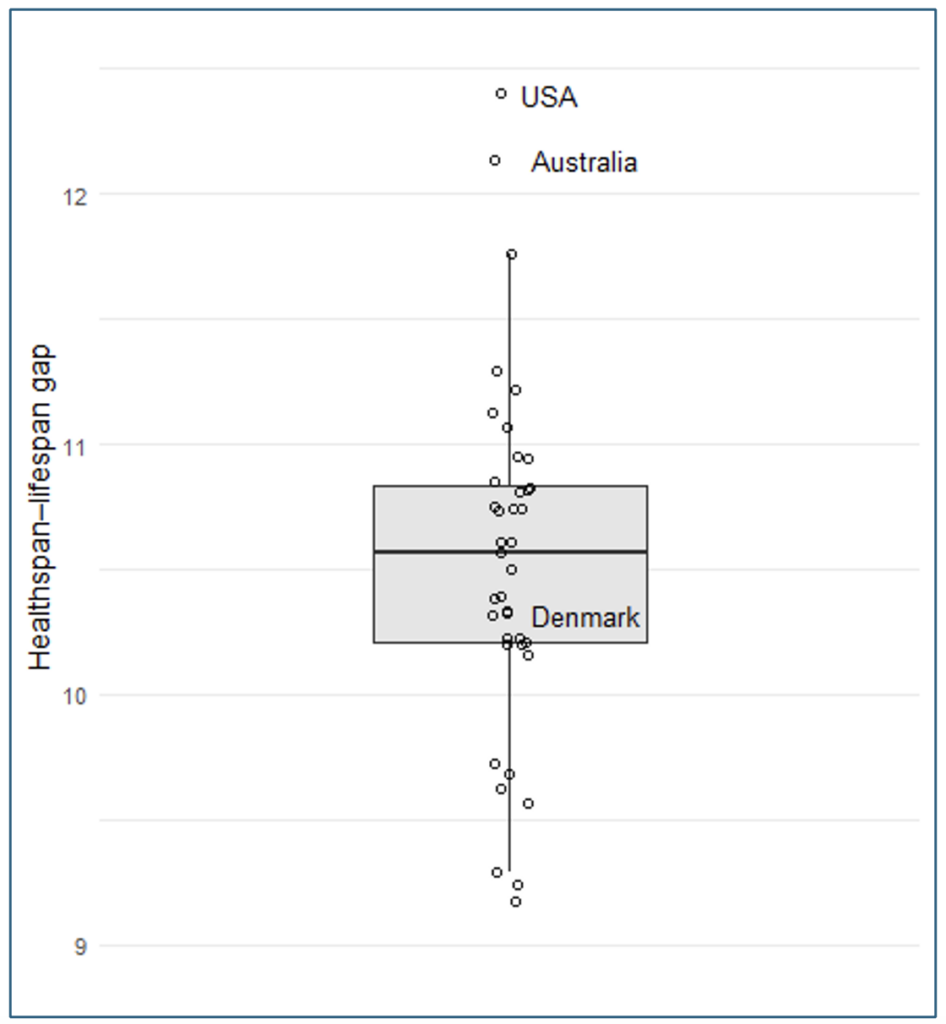

We take pride in our life expectancy of 83 years. But 12 of these are spent in poor health. That’s 14% of our lives – a clear outlier.

L Slawomirski. Source: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2827753 (Supplement 1). Only OECD countries shown

This is the predictable result of under-investing in prevention. We have a crisis in mental health. People languish on waiting lists for surgeries that shouldn’t be needed with better prevention. Avoidable hospitalisations cost us $7.7B a year. States and the Commonwealth battle over hospital funding instead of addressing what fuels demand in the first place.

We’re more obese and consume more alcohol than other countries. The only bright spot is smoking rates, where effective public health campaigns have cut rates dramatically, generating billions in savings and productivity each year. Investing in prevention pays off.

Denmark once had a system much like ours. In the 1990s, they decided to modernise: shifting investment from hospitals to prevention and primary care. Today they spend more on non-acute services and achieve excellent health outcomes.

Australia hasn’t made that shift for two reasons.

First, complacent politics. Acute care is an easy political sell. Voters associate health with hospital beds and MRI scanners. Prevention, by contrast, concerns things not happening – often years after an intervention. So, politicians prefer cutting ribbons to announcing a sugar tax.

Secondly, we’ve let the foxes run the henhouse. Policy-making is dominated by the medical profession and industry groups, while the public has little voice. Highly paid acute specialties, who benefit most from the current arrangements, wield the most influence. Status and professional identity matter, but mostly it’s about money: every dollar of health expenditure is someone’s income.

Prevention is profitable too – but its returns flow to everyone through wellbeing, productivity and growth. It doesn’t enrich a small number of powerful stakeholders. The system is working exactly as designed, and any threat can provoke political fury.

To avoid drifting further toward the US – more spending for worse health – we need to change course. Four steps would make a meaningful difference

The system belongs to the public, not to industry. Clinical authority shouldn’t mean political authority. Major decisions about funding, regulation and system design should prioritise citizen interests, not those of the most powerful lobbyists.

States currently control public hospitals but have limited influence over what keeps people out of them. They need responsibility – and funding powers – across the entire health journey, from prevention to aged care. It would be politically difficult but transformative.

These keep people off waiting lists and out of hospital. Remuneration for primary care workers must align with acute specialists. Funding should prioritise access for vulnerable communities and encourage collaboration across disciplines.

Private health is a policy choice, not an inevitability. The sector should justify its $7.8 billion annual taxpayer subsidy. That means eliminating waste: unnecessary diagnostics, low-value interventions and extended hospital stays. Specialists must be transparent about fees and outcomes; without this, “patient choice” is meaningless.

Claims that the private sector relieves pressure on public hospitals should be put to bed. Insurer–providercollaboration should be encouraged, particularly where it supports prevention and reduces hospitalisation.

The good news is that this requires no additional money.

Acute care is expensive. Redirecting a fraction of current funding toward prevention and primary care would deliver more health per dollar. We will always need hospitals – but not as the foundation of the entire system.

The vested interests will resist change. But the current arrangements are failing us. If we want a healthier, sustainable system, political courage is no longer optional – it’s long overdue.

Luke Slawomirski is a health economist and former clinician. He has worked for State and Commonwealth governments, and the OECD in Paris. He is a Visiting Lecturer at Imperial College London and is completing a PhD with the Menzies Institute for Medical Research at the University of Tasmania.

The claim that half of voters rely on the Government for 'most of their income' that has been repeated across the media and by politicians, simply isn't true.