Photo: AAP Image/Darren England

Take a moment to imagine ‘a typical One Nation voter.’

If you’re imagining someone middle aged or older, you’re on the right track.

If you’re imagining someone who lives in rural or regional Australia, you’d be right.

Likewise, you’d be correct if you’re imagining someone with a TAFE qualification or high school education, rather than a university degree. But what about their gender?

I’d wager you’re probably imagining a man. And you wouldn’t be wrong, but nor would you be wrong to imagine a woman either.

There can be a tendency to see support for populist right-wing parties as being primarily driven by men aggrieved by either social change (feminism, immigration, ‘wokeness’ etc.), or economic disruption (loss of traditional blue-collar jobs, cost of living, housing prices and so on.)

This isn’t without basis: there is a massive gender gap in support for Donald Trump – recent data from The Economist/YouGov poll shows only 34% of women support the US president, compared to 47% of men. Meanwhile in the UK, YouGov’s data shows an 8-point gender gap in support for Nigel Farage’s Reform Party (Men: 30, Women: 22.)

But here in Australia, the data from our most recent Capital Brief/DemosAU polls show no such gender gap.

In our latest national poll of 1,933 respondents, 24% of women say they would vote for One Nation, compared to 25% of men. In terms of attitudes to Senator Hanson herself, the difference between men and women is similarly negligible: 36% of men have a positive view of her, compared to 35% of women. In terms of other pollsters, YouGov’s most recent release has support for One Nation equal among men and women at 25%, while Fox and Hedgehog points to a slightly larger 4-point gap (Men 23% – Women 19%).

So, what’s going on here? Perhaps the answer comes down to the obvious difference between Ms Hanson and Messrs Trump and Farage: She is a woman herself. Could it be that a right-wing populist party headed by a woman finds it easier to appeal to women than one led by a man?

If we look beyond our anglophone peers to Europe’s far-right, we can find some further evidence.

In France, for instance, exit polls from the 2024 European elections show 33% of women voted for Marine Le Pen’s National Rally, compared to 30% of men. In Italy, more women voted for Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy at the 2022 elections than any other party – they secured 27% of the vote among women, according to exit polls, and 26% overall.

This is a small number of case studies, but there’s clearly an argument to be made that far-right parties become more appealing to women when they’re led by someone they are more easily able to identify with.

Of course, it’s true that, over recent elections, women have been more inclined to support left-wing parties than men.

Our October/November MRP* showed Labor’s 2pp was 4 points higher among women than men (and women are much more likely to support the Greens – 16% vs 10%). But that still leaves a lot of women supporting parties on the Right. It’s also true that installing a woman as leader is not an automatic guarantee of strong support among women. Case in point: Sussan Ley and the Liberals.

And this could all change. With more than two years until the next election, there’s plenty of time for One Nation to alienate some cohorts, especially given the party’s newfound prominence. We also don’t know how the arrival of figures like Barnaby Joyce, Cory Bernardi, and whoever else has defected to One Nation by the time you’re reading this, will affect the equation.

For now though, I think we need to move away from gender-based narratives about One Nation’s support and focus on the key demographic cleavage points: age, education and location.

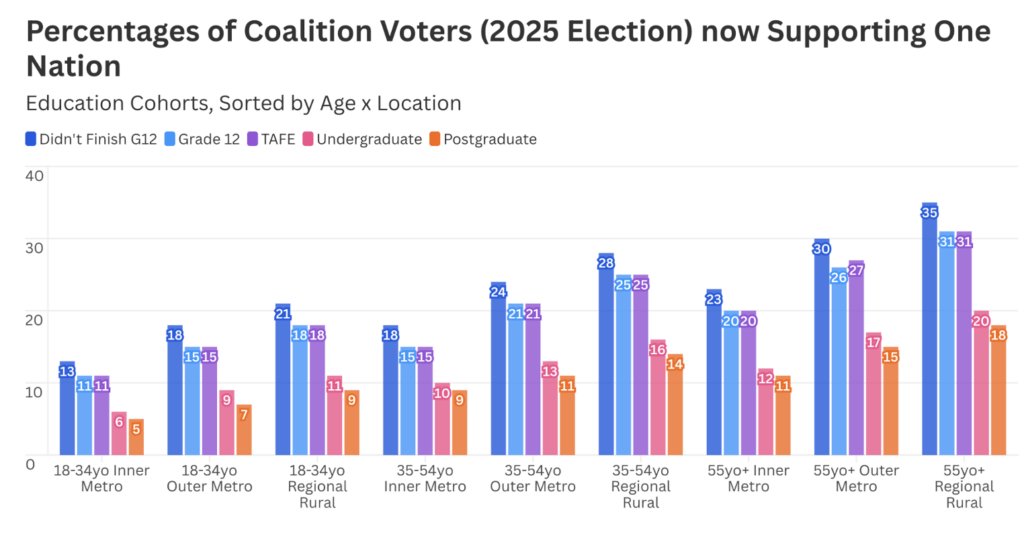

The below graph from our October/November MRP* model shows what is really going on here. This is a projection of the 2025 election Coalition voters switching to One Nation.

(*MRP – Multilevel Regression with Poststratification is an advanced form of statistical modelling based on large sample sizes that can yield yields better demographic analysis than conventional polling methodologies)

As of late last year (before the Bondi tragedy), around one in three previous Liberal/National voters living in rural or regional areas who didn’t finish high school, or who had a high school or TAFE education, said they would vote for One Nation. For those with a university education in the same area the number drops to one in five. At the other end of the spectrum, among Coalition voters aged 18-34 in inner metro areas, around one in 10 without a university education planned to vote for One Nation, compared to one in 20 with a degree.

The trend is also the same among Labor voters, albeit in lower numbers.

To recap, support for One Nation rises the further you move from the inner city and with older age, with a sharp divide between those who hold university degrees and those who do not. These are the demographic trends to focus on when trying to understand the drivers of One Nation’s recent surge and its electoral prospects

Evan Schwarten is a Director of DemosAU.