Thu 4 Dec 2025 06.00

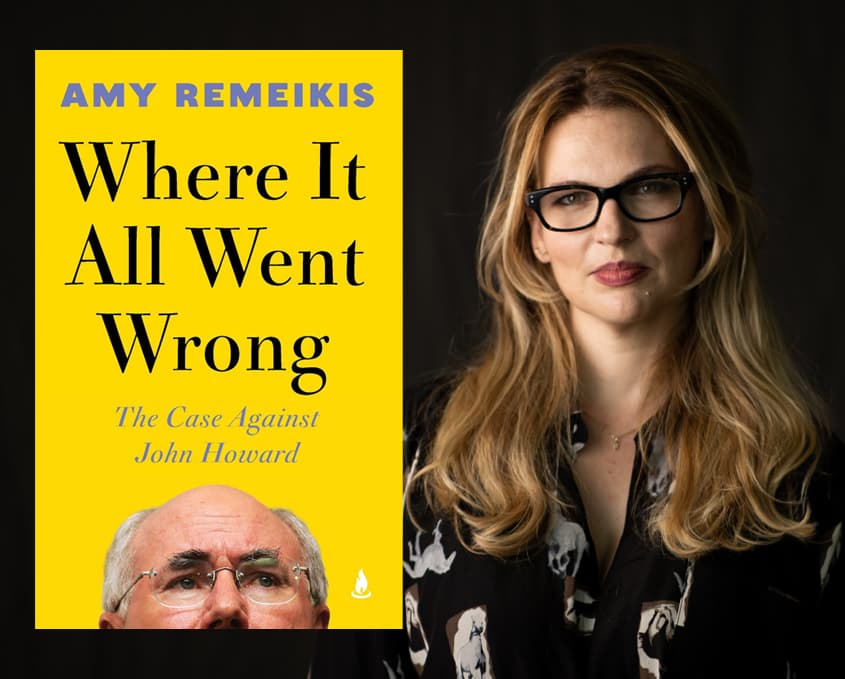

Sydney, December 15, 2004. Environmental activists protest outside the Australian Stock Exchange in Sydney against Gunns Pty Ltd which has served writs against 20 individuals and organisation seeking over 6 million dollars which the protesters are saying is an attack on free speech. (AAP Image/Dean Lewins)

On the last day of sitting for 2025 the federal parliament passed long-awaited reforms to the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act. This set in legislation an important shift toward stronger regulation on native forest logging. With an end (in 18 months) to decades of legislative gaps – most notably the exemptions created under the Regional Forest Agreements (RFAs), which had allowed native forest logging to sit outside nations environmental laws.

What was notable, apart from the deadline driven nature of the negotiations, was that the old stalking horse of so-called ‘green lawfare’ made yet another appearance on the Senate floor.

Senator Richard Colbeck reminisced on being one of the few who was in the parliament back in 1999, when the RFA for each state came into effect and created the perverse scenario of native forest logging being exempt from the EPBC Act. As the Senator reflected:

“I remember quite clearly the delight of the forestry industry, because the exemption… took away the continuation of green lawfare that was imposed on the industry… It was because of the green lawfare of environmental groups who wanted to use that to cost the industry out of existence… I remember the impact on industry by environmental groups, who we know don’t always tell the truth… It was done to mitigate the impact of that green lawfare.”

This narrative suggests that environmental groups and community members, many of which operate on self-funded small budgets and volunteer passion, wield disproportionate legal power capable of threatening industry viability.

Environmental groups do not have the capacity, financial resources or institutional incentives to pursue frivolous litigation. When community groups or conservation organisations bring a case, it is because significant environmental or procedural issues are at stake, and because all other channels for accountability and protecting the environment have failed.

Meanwhile, corporations have repeatedly used the legal system as a tactical tool to deter public participation. And this is where the story gets personal and political.

The most infamous example is the Gunns 20 case. In December 2004, the largest native forest logging company in the southern hemisphere Gunns Ltd filed a 216-page civil claim seeking millions of dollars in damages against 20 individuals and organisations, including myself.

This civil case is known in legal circles as a Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation (SLAPP) suit. The allegations were sprawling and ultimately unsustainable. The case collapsed after 5 years of litigation and enormous expense – not just for Gunns, but for the defendants.

Photo: Greens senator Bob Brown and environmental activist Louise Morris (left) leave the Supreme Court in Melbourne, Tuesday, April 3, 2007. A Supreme Court judge today threw out an original statement of claim in a lawsuit taken out against 20 environmental groups or individuals, including two Green party politicians, citing their ongoing damaging campaigns and other activities against the company. (AAP Image/Julian Smith)

But the Gunns 20 SLAPP suit was not an isolated incident. Subsequent to the Gunns 20 writ, Gunns Ltd issued a separate SLAPP suit against me as an individual linked to peaceful protest and advocacy.

Smaller operators followed similar strategies. In 2005 Harback Logging issued a SLAPP lawsuit against myself claiming that I had conspired with unknown people, on unknown dates to perform unknown acts. Try raising a defence against that!

It was a fishing expedition and effort at punching down on individual community members advocating for their forests. Unsurprisingly this court case went nowhere, and, like the others, fell over.

To be clear these cases were not attempts to resolve genuine legal disputes. They were civil cases, not criminal, and they were attempts to silence advocacy and chill civil society.

Each of these three lawfare efforts by logging companies carried the hallmarks of SLAPP action; exaggerated claims, vague allegations, ridiculous discovery demands. With the clear intention to exhaust time, resources and morale. Across these cases the through-line was unmistakable. Litigation was being used as a tool to silence individuals and send a chill through civil society.

This tactic has shaped environmental politics in Australia in ways seldom acknowledged. It has also created a parallel narrative pushed by some politicians and industry advocates: that it is environmental groups who misuse the law.

This claim, often described as “green lawfare” not just by Senator Colbeck but by mining industry CEO’s, heads of extractive industries and various members of state and federal legislature is not supported by evidence. Despite that it is frequently used to justify restricting community access to the law and justice when they are defending nature, culture and free speech.

The gap between this political rhetoric and the lived reality of those targeted by SLAPP suits is vast.

Why this matters for democracy

My experience defending against three SLAPP suits showed me how easily the legal system can be used to suppress dissent. Those cases were never about truth or harm. They were about power.

When corporations are able to use the legal system, and their incredible resources, to bully communities with SLAPP suits, freedom of speech and environmental protection erodes. With it also goes democratic accountability.

And when politicians frame community participation as a threat rather than a democratic right, they reinforce a climate where corporate lawfare can flourish.

Reforming the system

If Australia wants a fair and functional environmental governance system, reforms are urgently needed at the federal level. Most urgent is Federal anti-SLAPP legislation, to prevent corporations from using litigation to silence public-interest advocacy.

These reforms will not eliminate disagreement over environmental policy. But they will ensure those disagreements occur in a system where evidence matters, communities are heard, and powerful actors cannot use the courts and their large budgets to insulate themselves from accountability.

Louise Morris was defendant number 8 in the Gunns 20 SLAPP suit and went on to self-represent in 2009 in the final days of the case, which Guns Ltd eventually settled and dropped. Gunns Ltd declared insolvency and entered voluntary administration on September 25, 2012. Louise now works as an advocate at the Australia Institute.